Earth & Immune Series, Part 5 – Skin Battery

One of the cooler things I’ve noticed since grounding consistently is how fast minor injuries heal. Cuts, scrapes, lifting blisters, jiu-jitsu wounds.. they all recover quicker than they used to. Back then I didn’t realize it, but grounding was helping maintain my skin’s natural battery. That’s what this article is about.

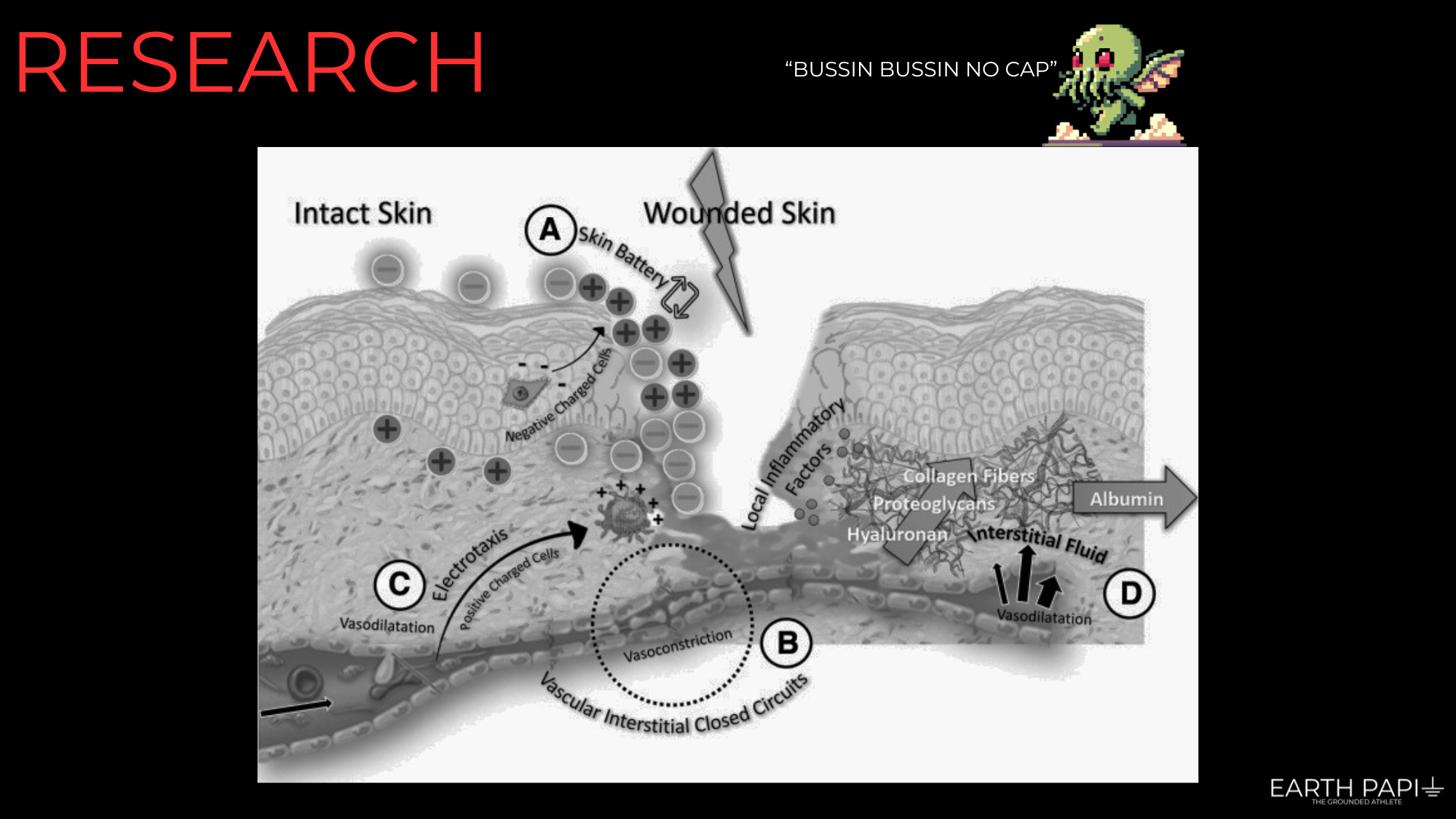

Wound healing isn’t just about immune cells and inflammation. It’s also about voltage. When skin is injured, the body generates an electrical potential across the wound site. This is known as the skin battery or injury potential.

The outermost layer of the skin, the stratum corneum, sits at a different voltage than the deeper dermis. In humans, this gradient averages about –23 millivolts. The polarity and magnitude vary depending on location, but the presence of this bioelectric field is consistent. When intact, it creates a directional signal that guides cells where to go. Disrupt this field, and you slow the healing process.

Experiments have confirmed this. When researchers reversed the polarity of this natural field by applying an opposing external electric field, wound healing stalled. This reinforces a simple but powerful idea - the skin’s native electric field is not noise, it’s a signal. It helps direct immune cells, guide tissue repair, and orchestrate inflammation resolution.

At the injury site, water, ions, and cells move through what's known as vascular interstitial closed circuits (VICC). Electrotaxis—or galvanotaxis—is the phenomenon where cells migrate according to charge. Positively charged cells like osteoblasts, monocytes, and corneal epithelial cells are drawn to the cathode, the negatively charged pole. Negatively charged cells such as macrophages and osteoclasts move toward the anode. This migration isn’t passive. It’s guided by the body’s own electrical blueprint.

There’s more. Inflammation changes the chemistry of the interstitium. Glycosaminoglycans, negatively charged long-chain molecules in the extracellular matrix, exclude albumin from certain regions. This shifts the local charge environment and contributes to the voltage gradient across the wound.

Connecting the body to Earth’s surface supplies electrons to the epidermis, effectively altering its potential. It lowers voltage fluctuations and stabilizes surface charge. This matters. A grounded body has a slightly negative surface charge, which helps maintain the native voltage difference between the skin’s outer and inner layers. When that difference is preserved, the electric field at the wound site stays intact. This supports electrotaxis and the directional flow of immune and repair cells.

If the skin becomes electropositive, whether from insulation or excessive exposure to artificial EMFs, the voltage gradient is compromised. Immune cells lose directionality. Healing slows down. Grounding reestablishes that field, allowing the body to preserve its natural electro-navigation system.

Of course, this is still a hypothesis grounded in biophysics, not just anecdote. But the physics check out. We’re electric beings. The skin battery is real. And grounding provides a way to maintain or restore the body’s default electrical state.

Efficient healing also depends on more than electric fields. Circulation and blood rheology matter too. Grounding has been shown to reduce blood viscosity and improve flow. This means immune factors and nutrients can be delivered more efficiently to injured tissue. Vasodilation widens vessels, further supporting this influx.

The bottom line - healing is electrical. Cells follow voltage gradients. Grounding maintains those gradients. When the body is reconnected to Earth, it doesn't just feel good. It works better.

As always, if you’re interested in learning more about grounding, check out Earth & Water.

References:

Farber PL, Isoldi FC, Ferreira LM. Electric Factors in Wound Healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2021 Aug;10(8):461-476. doi: 10.1089/wound.2019.1114. Epub 2020 Oct 6. PMID: 32870772; PMCID: PMC8236302.

Reid B, Zhao M. The Electrical Response to Injury: Molecular Mechanisms and Wound Healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2014 Feb 1;3(2):184-201. doi: 10.1089/wound.2013.0442. PMID: 24761358; PMCID: PMC3928722.

Ud-Din S, Bayat A. Electrical Stimulation and Cutaneous Wound Healing: A Review of Clinical Evidence. Healthcare (Basel). 2014 Oct 27;2(4):445-67. doi: 10.3390/healthcare2040445. PMID: 27429287; PMCID: PMC4934569.

Foulds IS, Barker AT. Human skin battery potentials and their possible role in wound healing. Br J Dermatol 1983;109:515–522

Borgens B. What is the role of naturally produced electric current in vertebrate regeneration and healing? Int Rev Cytol 1982;76:245–298

Farber PL, Isoldi FC, Ferreira LM. Electric Factors in Wound Healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2021 Aug;10(8):461-476. doi: 10.1089/wound.2019.1114. Epub 2020 Oct 6. PMID: 32870772; PMCID: PMC8236302.